This post is about an excellent recent paper by Luis Crouch and Deborah Spindelman, on the development of the Japanese and Korean education systems into world-class systems with world-class learning outcomes, despite war and colonisation – and what insights these stories hold for those improving education systems now.

It’s an inspiring paper because it examines in depth, not just the what and the how of education development in these countries but, most usefully, the why. It also succinctly despatches the myth that these highly successful countries are outliers with nothing to teach less developed nations. Then, in a bold step, it asks why this stellar trajectory did not happen in post-colonial African education systems and, surprisingly, suggests that donors such as UNESCO and the World Bank may have acted as unwitting inhibitors of education system development.

So, if you are involved in helping to reform or transform education systems in the global south (or north for that matter), you’ll find a wealth of insights relevant to system development today. If you’re concerned with policy and practice ; with top-down and bottom up ; with gender and disadvantage ; with equity and community….then you really need to read this paper.

But…..it’s 135 pages long !! 🫨 🫨 So, few practitioners are going to read it, which is a great pity. So, for the TL;DR group, I summarise below what I believe are the top three lessons that may be useful to present day education reformers. If that whets your appetite, there are a further five points at the end of the summary – and, of course, you can always read the paper itself 😊.

Summary

I believe three major points from this paper have very wide applicability for education reformers today.

First, National Purpose. For both Japan and Korea there was a long history, starting in the 19th Century, of engaging with western education systems, partly as a result of embarrassing military confrontation with the West. In both cases, the countries sent missions (study visits) to Western countries to learn what they could about the education systems there (these teams were wider than education, but in each education was a key focus). This interest in reforming their education systems gained added impetus at the end of World War 2 through the need for national rebuilding. Education was clearly understood to be a critical building block to develop society and the economy – but, that development was inextricably linked to a concept of national purpose, encompassing social cohesion, modernisation and infrastructure development.

The uncomfortable (for the liberal-minded) connections between national purpose and nationalism – especially the militaristic overtones in pre-war Japan – are confronted head-on in the paper. Post-WW2, amongst allied countries (and amongst donors, particularly UNESCO), there were real suspicions of nationalism, exacerbated later by the cold war (some echoes today). Nonetheless, the coalescing of disparate social groups and classes around a shared and articulated common national purpose is highlighted by the authors as perhaps the key element of the successful development of education in Japan and Korea. And that leads to the second point….

Policy Borrowing. Both countries were serious about learning, and borrowing, educational ideas. But, they borrowed what they thought was useful and ignored what was not ; they were active and conscious in their borrowing and borrowed on their terms and adapted in ways that made sense to them culturally and educationally. This makes it sound like a well-planned and linear effort : it was not.

What was borrowed was not fixed or unchangeable – in fact, as in many education systems, adoption of new approaches were often resisted, rejected or adapted. There were periods of contestation (by unions, by parents, by teachers) that took decades to play out. And, in these systems in particular, the influence of western values of individualism and learning autonomy were highly contested by those who believed a more social, familial, Confucian approach to education was more suitable / natural to these societies. For example, under the post-war influence of the US, Japanese education started to decentralise, but after 1952, when the occupying forces left, centralisation again became the dominant administrative direction.

Thirdly, what is most striking in this paper is the commitment Japan and Korea made to Equity and the decisions, made early in this process of reform, to prioritise equitable approaches. Competition and inequitable resource did, and do, still exist – but, by prioritising a kind of “no-child-left-behind” policy, and funding it, they set their education systems on a course which prioritised and expected high standards at all levels and did not tolerate differences of funding or opportunity – they deliberately raised the floor as well as the ceiling.

This began as a focus on equality of inputs (avoiding unfair regional funding bias for example, and gender differences) but quickly transferred to equality of learning outcomes – which then drove expectations of high standards. To give one example, in 1969 Korea eliminated the middle school entrance exam, closed the most prestigious secondary schools and introduced a lottery-based selection system for middle schools – all to prevent a widening equity gap. The impact of this focus is reflected in Gini Coefficient comparisons, see below.

As a paper this would be rich enough in insights if it stopped here. But, in a bold step the authors go on to analyse the post-colonial development of a number of education systems in Africa, asking why there is no comparable African example to rival Japan or Korea ? Despite well-intentioned commitments to education in several countries on realising their independence, none of the countries examined was able to develop a sustained commitment to education with internationally high-ranking learning outcomes.

The principal reasons suggested are threefold : 1/ a colonial history that created hard-to-unpick multi-track education systems for different groups or classes in society 2/ an inability to truly commit to equity as the foundation for education investment post-independence and to really fund it and 3/ the unwillingness of donors to influence, support, or prioritise education for national purpose for fear of seeming to support nationalism. It is this latter point where the authors suggest donors may have unwittingly hampered the development of education in these countries.

A final thought : remember the high hopes that were espoused by many educators that COVID would lead to a radical reset for education ; a new dispensation where countries would need to “build back better” ? It seemed to be the kind of shock which might move the world onto a different track. The story of these two countries shows what could have happened – and why it did not.

Those are my top three – for a further elaboration, and five more reflections on what this paper can tell us about current education system development, see below.

If you want to go straight to the full paper – click this link.

1. Purpose – more on donors

The paper focuses on multilaterals – principally UNESCO and the World Bank – using a textual analysis of policies and public plans to assess whether donors have supported governments advancing a “national purpose” agenda for fear of taking sides politically or being associated with nationalism. The conclusion is that an unwillingness to engage with this type of agenda may have unwittingly led donors to de-prioritise support to initiatives / regimes that could have had a transformational effect on education systems.

This probably overstates the agency of those donors whose funding is usually marginal in any education system (with some exceptions e.g. Malawi). They also do not cite any cases where this may have been a missed opportunity. Which is not to deny the point, but it may be equally true that donor competition, or lack of co-ordination, may have played a similar “dragging” role. It certainly adds to the authors’ case that neither JICA nor KOICA have been very strong advocates of the lessons their own history teaches in trying to support education development in other countries (though JICA’s ODA education policies are more consistent with Japan’s history).

2. Borrowing – more on exposure

The paper assesses many different types of “policy borrowing” (settling on this term after exploring many similar others, including policy learning/ attraction / negotiation / imposition / hybridisation / transfer etc.). But, in both Japan and Korea cultural exchanges, investigative visits outwards, inward delegations for educators etc. have taken place over long periods and had significant influence. Not all of this influence was positive and some of it rightly critical e.g. the Iwakura Mission of 1871-3 thought the elementary education systems in the UK, France and Russia to be terrible compared to the USA and Prussia.

What is common between the Iwakura Mission and a similar mission, Bobingsa, from Korea (both “study visits” in the 1870s/80s), and subsequent assessments by Japanese and Korean educators, is the control and focus of the agenda. These countries set out to learn, borrow and adapt on their terms according to their own criteria – and they did so in a planned and systematic way with political support. They borrowed from a place of strength, understanding their own system’s weaknesses and strengths, and using that knowledge to assess, reject or adapt foreign educational approaches.

The authors cite an interesting statistic : between 1946-1976 40% of all US aid to Korea was in the form of long-term technical assistance (p65). That is high by any standards e.g. long-term large-scale education projects nowadays funded by bilaterals might reach 20%. Were these really educators or a euphemism for military personnel ? If really the former, what is the significance of this in the development of education in Korea ? The impact of so much educational expertise, over a thirty-year period, on Korean educators is likely to have been significant but in ways that may be intangible.

3. Equity – more on gender

The emphasis on equity, found in both Japan and Korea is not uniform across the education system – in fact both countries are bywords for cramming / extra-curricular study and intense competition to reach the most prestigious schools. But, when it comes to the basics of the primary and secondary schooling system this equitable approach seems to have been a defining principle. In other words, the foundations of the system that have led to very high standards in internationally comparable testing such as PISA / TIMMS etc., were deliberately designed to be equitable – even if post-secondary and higher education were not as egalitarian.

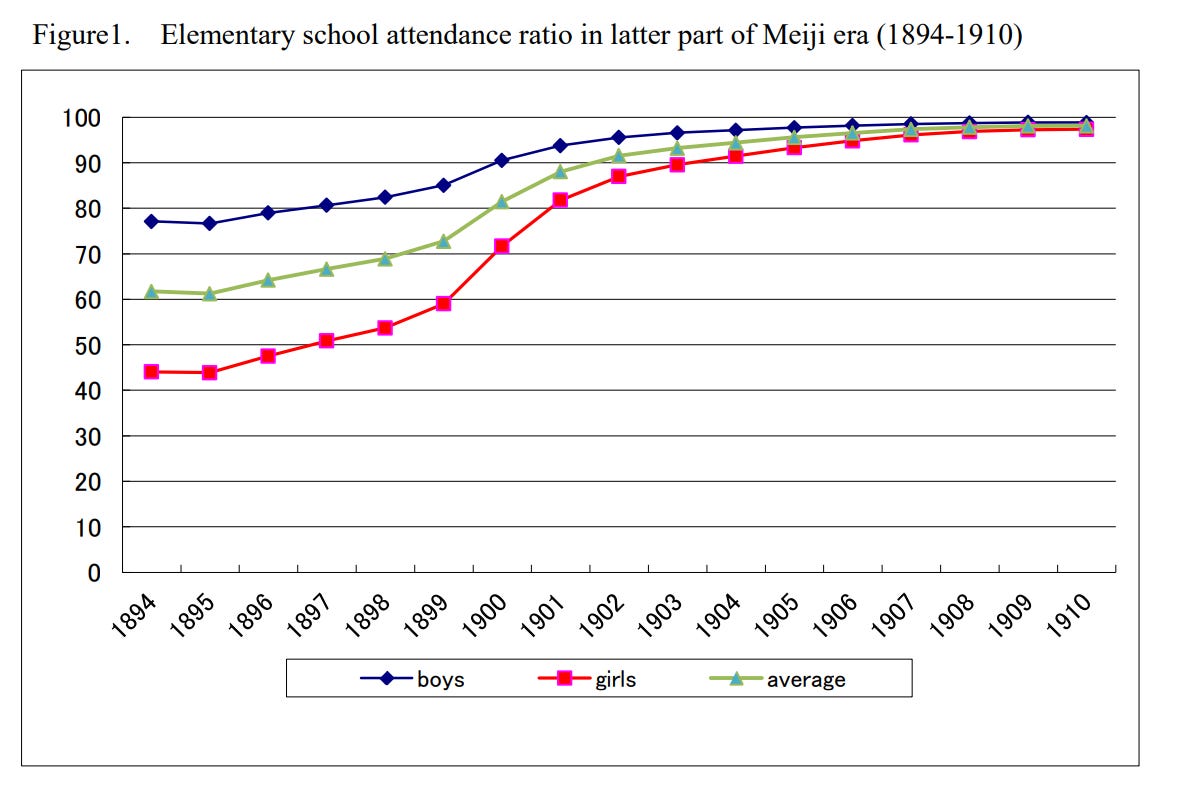

A relatively lightly-commented feature of the paper is that this approach to equity benefited girls as much as boys, unusual in such strongly male-oriented societies as Japan and Korea. In Japan for example, within only about ten years, girls’ and boy’s enrolment was almost indistinguishable (see Figure 1 below).

Source : Gender Equality in Education in Japan (201403GEE.pdf (nier.go.jp))

4. Cultural Uniqueness

This is a big question mark and the authors address it directly. There is a tendency to dismiss the lessons from Korea and Japan as being inadmissible evidence due to cultural differences. Successful examples, particularly at scale from Asian countries, are dismissed as outliers and lacking insight for countries in Africa. This is intellectually lazy. As the authors state :

“While there may be something to this, our finding strongly suggests instead that many of the features that seem culturally-bound are actually created or reproduced by the schooling system via not only a curriculum but a teaching style that results in those features.” (p132)

They go on to assert :

“So, it may be that the notion that because culture is determinative, there is nothing to borrow, may just be a bit of an excuse to justify not doing the hard thinking and hard focusing that Japan and Korea did over decades in many native-led commissions, teacher networks, endogenous journals and magazines, and well-led Ministries of Education but with contestation on deeply pedagogical issues (not just bread and butter issues) between and from interest groups including the teachers’ unions.” (p133)

These are important points that ally closely with the paper’s dissection of “policy borrowing” and the way both countries undertook this. What resulted from this exercise was not a quasi-American education system in Japan or Korea, but a Japanese / Korean education system that showed clear borrowing from other systems contextualised within their own national system.

There is one aspect of culture that is not unique to Japan and Korea, but definitely has had an impact, and has made the task of reform easier : homogeneity. The fact that both countries are, to a large extent, ethnically and religiously homogeneous, has meant lower costs in rolling out national programmes (fewer languages to print textbooks / train teachers in etc.) as well as greater ease of transferring / substituting teachers etc.

5. Time – taking the long view

It took Japan and Korea about 50-60 years to go from an average of 1 year of schooling for citizens to 6 years. This is about the same length of time as a composite of Malawi, Kenya and Uganda took. The authors comment that :

“…it is interesting to note that this process of transition has taken about as long in today’s context, even with all the foreign aid and international goals, as it did for countries that had no aid and no global goals” (p24).

Why then should Japan and Korea be held up as examples ?

“The answer is that Japan and Korea achieved a large increase in the number of years of schooling quickly, but did so without neglecting both excellence…and equality”. (p25)

6. Champions and Windows

All change needs champions to drive reform and take advantage of windows of opportunity. Only a few individual names are mentioned in the paper, but a more detailed analysis of each aspect of reform, over the 200 years or so covered, would identify key individuals who drove forward change, or resisted it, including groups (teachers, unions, parents) who played important roles at key times in pushing development. Though they are unsung heroes and villains in an analysis at a country level, they are the essential players in any narrative of change up to the present day – and modern reformers trying to implement education reforms need to identify those champions (individuals and groups) – from community to country levels – and harness their support.

And lest these excavated points from the paper seem to describe a linear progress, read Section 4 on the “Historical narrative on Japan or Korea”, even if you only skim the rest of the paper. These are well-crafted summaries of the forwards and backwards of educational progress, the ebb and flow of such a contested area. They pick out what now, with hindsight, seem to be the windows of opportunity taken at critical junctures.

For example, in Japan a major westernisation initiative in 1872, The Fundamental Code of Education (Gakusei) lasted only 18 years before being rolled back in 1890 by the Imperial Rescript on Education that introduced a more militaristic purpose to education (ironically perhaps, a period that witnessed massive increases in enrolment and gender parity). The Imperial Rescript was itself briefly challenged in the Taisho democracy period of 1912 to 1926, which swung to a more progressive approach to education, before that too was pushed back by the nationalistic and militaristic forces of the 1930s. Post-war, the pattern repeats, in different shapes. Most countries have this kind of pattern, rarely is progress linear on one direction, except perhaps in autocracies.

7. Seismic shocks

It’s difficult to escape the observation that so much positive change was brought about by seismic events – particularly military confrontation – but not necessarily in a causal line, sometimes the impact is delayed. But, for reformers today seismic shocks / wars are not a policy option to entertain (and our most recent shock, COVID, seems not have been seismic after all, at least not positively). Can historical analysis of education development give us insights into peaceful transitions i.e. do they take longer, are they shallower etc. ? And, are the radical examples we see in cases like Japan and Korea replicable without the sorts of shocks both countries suffered ?

8. Funding and Efficiency

Given that in both Korea and Japan, rapid expansion of the quality education system occurred immediately after colonisation (Korea by Japan) and war (both) the question also arises of how this was funded ? The paper notes that the GDP per capita spend in the period of expansion was only c. 3% in Japan and 2.3% in Korea cf. 5.6% in Kenya and 4% in Malawi (p28).

Nonetheless, In Korea for example, the primary education budget rose from 9.3% of the government budget in 1955 to 15.2% in 1960. Post-secondary funding doubled in the same period. Much of this was provided in the form of American budgetary support ($12.6bn between 1946-76) – of which a substantial amount was spent on infrastructure including schools, and as noted before, 40% on technical assistance. What the paper suggests is that there was considerable efficiency in education spending in both countries – including double shifts, use of temporary buildings for schools, acceptance of private sector provision to enable coverage and growth etc.

But, it was not just efficiency, there was also intentionality : “…(less fiscal effort, more focus and intentionality in a qualitative, managerial or social sense…” (p31). Speculatively, the authors wonder if this relatively low spend is possible in contexts, like post-colonial Africa, where there are no seismic shocks and no strong or coherent national purpose driving education development. Is higher spend a peace premium ?

Conclusion

I could say a lot more, but if you’ve made it this far you have the stamina to read the paper ! For anyone with a genuine interest in education reform, who wants to understand the ingredients that lead to successful system change, in whatever context you are in, this paper has a great deal to offer. Click here to go to the full paper.